Chatter on Mainland China, Taiwan and Geopolitical Legacies: Tensions, Ruptures and Continuities

Modern Chinese history is marked by a succession of geopolitical upheavals, ideological conflicts, and identity tensions, of which the relationship with Taiwan is both a symptom and a catalyst. Since the 19th century, China has faced imperialist aggression, colonial humiliation, a devastating civil war, and a radical ideological revolution. Within this context, Taiwan has become much more than an island: a refuge for nationalists, a laboratory of capitalist development, and today, a focal point of Sino-American tensions.

This text offers a chronological and analytical exploration of these major events, highlighting the continuities, fractures and transformations that have shaped two regimes, two narratives, yet one shared civilisational matrix.

I. China and the Imperialist Powers (19th – Early 20th Century)

Weakened in the 19th century by civil wars, technological backwardness, outdated agriculture, a moribund industry, and a declining army, China became prey to imperialist ambitions. Russia, Germany, and above all Japan, imposed their domination through military force and a series of deeply inequitable treaties. The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) marked a decisive turning point. The Treaty of Shimonoseki, which formalised its outcome, forced China to:

- Open several ports to Japanese trade and exploitation;

- Relinquish its suzerainty over Korea;

- Cede Taiwan and part of Manchuria.

Taiwan, under Japanese rule for half a century, was subjected to a policy of systematic Japanisation: suppression of the Chinese language, expropriations, incentives for Han emigration, cultural repression, and even ethnic cleansing. This unequal treaty remains a vivid humiliation in Chinese collective memory.

II. The Sino-Japanese War, Resistance and Civil War (1937–1949)

The Japanese invasion of 1937 sparked an unprecedented resistance, embodied by two opposing forces united against a common enemy:

- The nationalist army of Chiang Kai-shek, heir to the 1911 republican revolution, mainly active in urban centres;

- The communist army of Mao Zedong, rooted in rural areas and supported by the peasantry.

The People’s Liberation Army, emerging from rural society, gained prestige due to its closeness to the peasants it defended. Conversely, the abuses committed by nationalist troops against civilians eroded their legitimacy.

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, the civil war resumed. The United States supported the nationalists, while the USSR, distrustful of the “peasant communists”, unsuccessfully attempted to reconcile the two sides. China was recognised as a victorious power and, with American backing, secured a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council in the name of the Republic of China.

III. Taiwan: Nationalist Refuge and the Genesis of the “Chinese Schism”

Key chronological milestones:

- 1945: Taiwan is returned to China following Japan’s surrender.

- 1949: Nationalist defeat and retreat to Taiwan with 2 million soldiers, officials, civilians, as well as gold reserves and national treasures. Taiwan, then home to 6 million inhabitants, mostly Han Chinese, becomes the centre of the Republic of China.

- 1952: Japan officially recognises Taiwan’s return to China.

- 1953: End of the Korean War.

- 1958–1960: The Great Leap Forward — a major economic and humanitarian disaster (26 million deaths).

- 1964: France recognises the People’s Republic of China as the sole legitimate China.

- 1966–1976: Cultural Revolution (20 million deaths).

- 1971: The PRC replaces Taiwan at the United Nations.

- 1972–1973: Sino-American rapprochement, lifting of sanctions, and Nixon’s visit.

IV. Two Chinas, Two Visions: Ideology, Exile and Survival

The retreat of the Nationalists to Taiwan marks the beginning of a lasting duality: one China, two regimes.

- The People’s Republic of China, founded by Mao, follows a revolutionary communist path.

- The Republic of China (Taiwan), led by the Kuomintang, claims the republican legacy of Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925), the man who ended China’s feudal era.

Amid the Cold War and the policy of containing communism, the United States supports Taiwan politically, economically, and militarily. The island becomes a manufacturing outpost for the American economy. Polluting industries, such as Formosa Plastics, are established there, and Western culture is transmitted through the presence of the US Seventh Fleet’s marines.

American aid, combined with the arrival of highly skilled refugees, bold agricultural reforms, and a fierce collective determination, propels Taiwan into the ranks of global technological powers. Literacy reaches 100% by 1980, and TSMC becomes a key player in the global semiconductor industry.

In 1985, during a visit by Crédit Lyonnais Taipei, TSMC’s president—a graduate of a prestigious American university who speaks standard Mandarin—remarked: “Nations that eat with chopsticks tend to outperform those that eat with forks in electronics.” A playful reference to Ricardo’s simple theory of comparative advantage, sometimes forgotten today.

V. Chiang Ching-kuo: From Trotskyism to Taiwanese Democracy

The son of Chiang Kai-shek, Chiang Ching-kuo(1910–1988) embodies the complexity of Chinese trajectories. Educated in the USSR (1925-1937), fluent in Russian, a former Trotskyist married to a Russian woman, he was responsible in 1949 for transferring China’s gold reserves and national treasures to Taiwan. He also ordered bloody anti-communist purges.

During his presidency (1978–1988), he initiated the democratisation of Taiwan. Under his leadership, the Kuomintang laid the foundations for political pluralism. A singular path blending authoritarianism, modernisation, and gradual openness.

VI. Mao, the USSR and the Pursuit of Self-Sufficiency

In 1949, the United States imposes a strict and total embargo on Communist China, lasting 25 years. Ostracised by the West and increasingly estranged from the USSR, Maoist China adopts a radical stance to assert itself against the Soviet giant. The Maoist regime is completely isolated. It survives this political and economic isolation at the cost of millions of lives.

The Great Leap Forward (1958) ends in disaster. Based on poorly understood techniques implemented by a largely illiterate population, poor planning choices lead to devastating famine. This pride-fuelled initiative claims 26 million lives. Yet the regime remains in place. From this tragedy, the PRC learns to craft five-year plans with ruthless efficiency.

VII. The Korean War and Nuclear Ambitions

During the Korean War (1951–1953), China—lacking diplomatic recognition—directly confronts American army.

US nuclear threats against China (Manchuria) and North Korea drive Beijing to develop its own hydrogen bomb, successfully acquired by 1967. This context helps explain the enduring nuclear ambitions of North Korea.

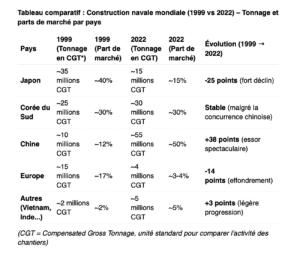

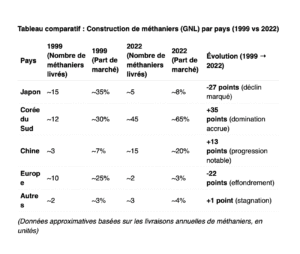

The historical, cultural, and economic closeness between China and the Korean peninsula fosters strategic ties with both North and South Korea. From 1980 onwards, China benefits enormously from Taiwanese and South Korean industrial relocations. Previously negligible due to historical reasons, China’s shipbuilding industry becomes a major global sector. These two countries undoubtedly contributed to China’s rise. Hong Kong and Singapore, meanwhile, brought their financial expertise, playing a key role in the 1990 creation of stock exchanges—capitalist symbols—in Shanghai and Shenzhen.

China’s development also involved learning from its Asian neighbours. Nonetheless, relations remain complex between “Communist” China and the bloc of Asian countries under Western influence.

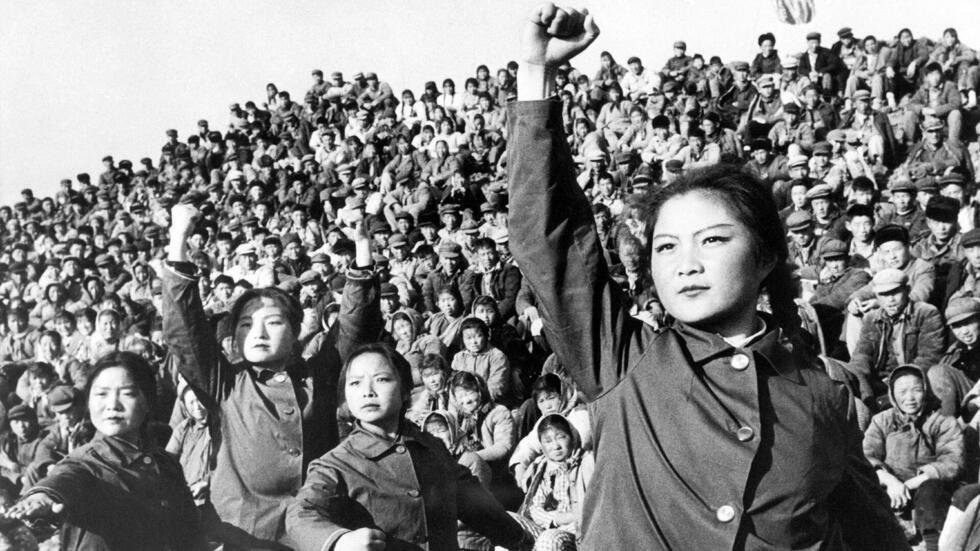

VIII. Cultural Revolution: Chaos as a Tool of Power

The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) marks a period of intense ideological violence in a world already in turmoil (1968 in France). Mao mobilises the youth—transformed into Red Guards—to weaken elites inclined towards a Soviet-style rapprochement with the West. The USSR, fascinated by Western prosperity and economic success, is labelled “bourgeois revisionist”.

Grim re-education camps emerge for intellectuals and experienced officials. The disorganisation of the economy and healthcare system is total, resulting in around 20 million deaths.

Xi Jinping, then a teenager, is himself sent for re-education after his father—one of Mao’s comrades—is imprisoned. This formative experience likely shapes part of his political ethos and influences his eventual rise to power in 2012.

The sidelining of Jack Ma, Alibaba’s CEO, once flamboyant in his early days, can be understood in light of this logic of ideological and behavioural refocusing, promoting elites more aligned with Confucian ethics. Having completed his period of ‘re-education’, he is now (following a meeting with Xi on 18/02/2025) emerging as the leading figure of the technological industry. The Jack–Jinping duo is set to play a central role in the implementation of the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026–2030).

IX. From Isolation to Diplomatic Opening (1971–1976)

In 1971, the PRC joins the United Nations as the RC with the support of many Southern countries—particularly in Africa—whom China had supported during its period of isolation. This “South-South” diplomacy remains a key component of China’s foreign relations and partly explains its current economic success with African nations.

In 1972, betraying the Republic of China, the United States begins rapprochement with Beijing: partial lifting of sanctions and Nixon’s visit in 1973. This opening, motivated by a desire to isolate the USSR, marks a significant Cold War turning point. While Soviet leaders were ready to offer their hearts, bodies, souls, and rare earths to the West, American strategists were betting on “those miserable Chinese peasants.” A winning bet: today, it is they who finance the American lifestyle.

Conclusion: Resistance, Rupture, and Ambiguity

Modern Chinese and Taiwanese history is marked by violence, exile, ideological rivalry, and geopolitical realignments. Two regimes, two narratives, two claims to legitimacy, but one people – the Han – now engaged in a confrontation where economic interests are deeply intertwined.

As General de Gaulle said in 1964:

“China is a gigantic thing. It is there. To live as if it does not exist is to be blind.”

Since the 1911 revolution, China has become a living synthesis of Confucian, Mongol, Manchu, and Marxist legacies. Marxism—an originally Western concept and philosophy—has now been fully absorbed into the DNA of the Chinese “Communist” Party. With Mao’s death in 1976, the Chinese dragon – this political and civilisational mutant – finally enters the modernity of the twentieth century.

Yet in the Chinese zodiac, it is not the dragon that opens the zodiac – it is the rat, the cleverest of them all.