Two Adolescent Tragedies: Shakespeare and Cao Xueqin

I. A Universal Enigma: Love Confronting the World

Two great works, emerging from distant traditions, raise the same question: why can absolute love never be fulfilled in the world of men?

- Romeo and Juliet, a play by William Shakespeare (1564–1616).

- The Dream of the Red Chamber (Honglou Meng), a novel by Cao Xueqin (1710–1765), where the figures of Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu shine.

In Verona, two adolescents choose one another despite an ancestral family hatred. In a Chinese imperial household, the Red Chamber, two cousins discover within themselves a debt of eternity binding them to an impossible passion. Separated by time, space, and culture, these narratives nevertheless probe the same enigma: what becomes of ideal love when it collides with social logic, violence, or fate?

To compare these two tragedies is to restate the beauty of their plots, to underline their resonances — adolescent love, revolt against established order, the fragility of the lovers, the ambiguity of spiritual guides — and to question what their differences reveal: two worlds brought together by love, yet profoundly distinguished by their symbolism.

II. Verona: The Blazing Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet

A sudden passion

In Verona, the Montagues and the Capulets, noble houses, are consumed by an obscure and hereditary hatred. Romeo, seventeen, encounters Juliet, thirteen, at a ball: love is born at once, absolute and irrevocable. But family violence intrudes: Tybalt, Juliet’s cousin, kills Mercutio; Romeo avenges his friend and kills Tybalt. The tragic course is set.

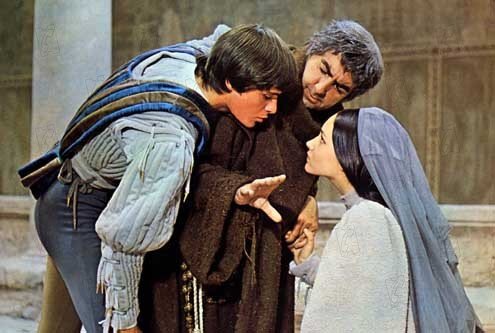

The priest’s stratagem

Friar Laurence, believing he might reconcile the families, secretly marries the young couple and devises a stratagem: Juliet will take a potion that simulates death. Yet illusion turns to disaster. Romeo, convinced she has truly died, poisons himself. When she awakens, Juliet, finding Romeo lifeless, takes her own life.

The suspicion of sacrilege

Their double death seals a reconciliation that comes too late, leaving behind the suspicion of sacrilege: in seeking to imitate the Christian mystery of Resurrection, the friar may have transgressed a forbidden limit. Thus the imprudence of a spiritual guide, too hasty in action, hastens catastrophe.

III. The Imperial Household: The Extinguished Dream of Jia Baoyu and Lin Daiyu

Mythic origins and the neutrality of monks

At the edge of myth, when heaven was still under construction, a stone was left aside — useless, gnawed by regret. At its foot, a fragile plant blossomed, adorned with crimson flowers. Moved by its fleeting grace, the rock watered it with pure spring water; in return, the plant vowed to it an eternal debt.

Centuries passed. A monk and a Taoist encountered this stone, now endowed with consciousness and eager to taste human passions. They warned it: Attachment is suffering, illusion is pain. To no avail. Already divining the tragic end, they did nothing to dissuade it. On the contrary, with a strange indulgence, they let its dream unfold and even aided it: beneath their ritual gestures, the rock became a radiant jade and descended among men, followed by the plant, resolved to repay its debt of water.

Thus was born Jia Baoyu, “the precious jade”, a singular child who entered the world with a stone in his mouth. A free and dreamy spirit, he grew up resisting Confucian rigidity, preferring poetry and the company of young women. One day, his orphaned cousin, Lin Daiyu, entered his life: melancholy, delicate, a beauty whose gaze seemed veiled with tears. From the moment they met, Baoyu recognised in her a familiar presence, as though echoing from another world, another life.

A poetic passion

Their love, woven of confidences and shared verses, blossomed in secret within the Garden of Delights. But the Jia family, anxious for its rank, imposed upon Baoyu a reasonable union with Xue Baochai, a beautiful, balanced, and virtuous young woman. Learning of this betrayal, Lin Daiyu slowly faded, consumed by grief, as if each tear repaid the immemorial debt of water.

Struck down, Baoyu lost all joy in life. After the downfall of his family, he renounced everything, abandoned his jade, and vanished into the mists of the Buddhist path, freed from his illusions. Thus ended the dream: a passion born under heaven, broken by men, dissolved in impermanence.

IV. Resonances, Contrasts, and Lessons for Today

What unites them

- Adolescent, absolute love — Romeo and Juliet, like Baoyu and Daiyu, love in the blaze of youth.

- A love against convention — The former defy family hatred; the latter collide with tradition’s weight.

- Fragility and tragic destiny — Juliet poisons herself; Daiyu wastes away in melancholy.

- The failure of spiritual guides — Friar Laurence, through recklessness, precipitates disaster; the monk and the Taoist, through neutrality, let the drama unfold.

What sets them apart

- Nature of the obstacle — External violence in Shakespeare; social constraint and fragile health in Cao Xueqin.

- The style of love’s bond — Carnal, blazing passion in Verona; slow, poetic, spiritual intimacy in China.

- The role of death — A brutal coup de théâtre in the West; a gradual extinction and religious path in the Red Chamber.

- Symbolic dimension — One embodies the universal power of love; the other reveals the world’s illusion and the vanity of attachments.

When Love Becomes a Key to Encounter

These two tragedies reveal far more than the fate of lovers: they reflect two cultural sensibilities.

- In the West, love is lived as a blazing, heroic force: Romeo and Juliet defy the world, the individual asserting freedom against society.

- In China, love unfolds in time, imbued with poetry and melancholy: Baoyu and Daiyu burn in silence, harmony of the group prevailing over individual impulse.

These contrasts illuminate cultural encounters:

- The West esteems frankness of emotion, direct expression, open confrontation.

- Classical China privileges restraint, allusion, social balance, sometimes at the cost of silence and sacrifice.

For the traveller, whether Chinese in Europe or Western in China, this double lesson remains precious:

- The Westerner will discover that indirection and modesty may express as much intensity as a fiery declaration.

- The Chinese visitor will understand that direct passion and frankness are not excesses, but proofs of sincerity.

Thus, these tragedies are not merely literary masterpieces: they are cultural mirrors. Love, whether uttered in a cry or a murmur, in blazing passion or melancholy, always expresses the same universal aspiration: to be bound to another.

A Political Lesson and a Burning Contemporary Relevance

But they also offer a political lesson: the imprudence of a spiritual guide too hasty, like the silent inertia of others, leads to ruin. The neutrality of sages who merely warn without intervening lets the drama unfold. Their silence, no less than the friar’s recklessness in Verona, becomes complicit in misfortune.

Between rash action and timid inaction, tragedy arises.

This dilemma speaks powerfully to our rulers today:

- To intervene too hastily is to risk worsening a crisis, as is sometimes seen in the rashness of certain economic, diplomatic, or military decisions.

- To do nothing is to allow social, ecological, or international fractures to deepen until they sweep all away.

To govern is not to choose between action and abstention, but to discern the right moment and the proper measure. The art of power, like the art of love, requires lucidity of timing, the patience of listening, and the courage to act at the right instant.

This demand finds direct resonance in today’s world: on 24 September, Typhoon Ragasa devastated Taiwan, causing immense damage. It would be fitting for the leaders of mainland China to offer unconditional aid to the island’s population. Beijing possesses every logistical, medical, and human resource to assist its “brothers on the other side of the strait”. Such a gesture, undertaken without calculation, would embody what it means to act at the right moment: to transform a trial into an opportunity for rapprochement, and to make lucidity and generosity the true art of government.