Story of Jade

The Extraordinary Story of Jade: from the Memoir of a Stone to the Poetry of Souls

The Mythical Genesis of the Stone

Once upon a time, in immemorial mists, there existed a singular stone destined to mend the vault of heaven. Yet, deemed superfluous among the 36,500 other blocks, it was cast aside. This stone was no ordinary rock: it spoke, it travelled, it dreamed. And yet, it felt useless and alone.

One day, a Buddhist monk — the symbol of renunciation — and a Daoist priest — the figure of mystery — came upon it. Both instantly discerned the stone’s transcendent essence. Yearning for glory, for luxury, and for the “wealth and honours of the world of glittering dust,” the stone implored to descend among mankind. The monk warned it:

“Nothing beautiful exists without flaw. You shall taste joy and vanity, but one day you must return to your original form.”

Then, through a secret ritual, he transformed the stone into jade of radiant purity, polished until it could rest in the palm of a hand. Upon this precious gem he engraved a few mysterious characters, sealing its exceptional nature. Taking the jewel with them, the monk and the priest vanished in a whirlwind.

Thus began the Memoir of a Stone — the original title of Cao Xueqin’s (1710–1763) masterpiece, later known as The Dream of the Red Chamber (Honglou Meng), the pinnacle of classical Chinese literature.

Jia Pao-Yü: the Incarnation of Jade

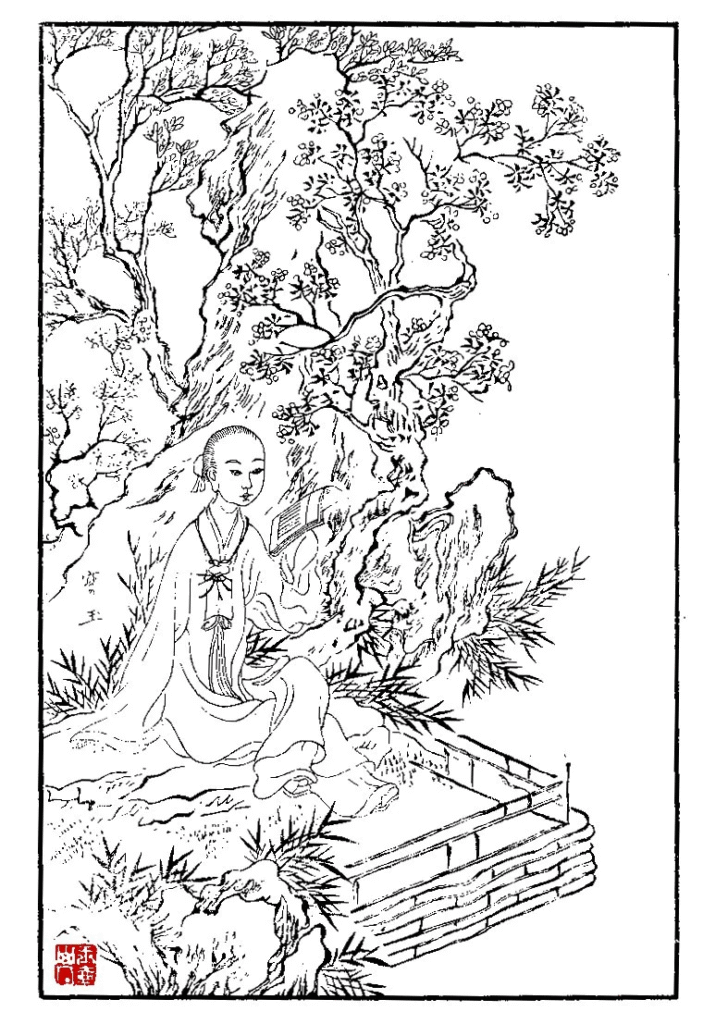

Centuries later, within an illustrious aristocratic family close to imperial power, a child was born. He was named Jia Pao-Yü (贾宝玉 / 賈寶玉, “Precious Jade Jia”), for he came into the world with that talisman of jade clasped between his lips. From that moment on, the young man’s fate was bound inseparably to this celestial stone.

Pao-Yü is portrayed as an adolescent of delicate, androgynous beauty: a fair complexion, translucent skin, fine brows, bright and dreamy eyes, lips as pink as those of a maiden. Everything about him embodies the fusion of yin and yang — a fragile grace, an inner radiance. His slender frame, his movements imbued with elegance, reveal a sensitive nature, at once vulnerable and refined. Above all, he always wears at his neck this supernatural jade, talisman of his innermost being and harbinger of his destiny.

Lin Tai-Yü: the Dark and Fragile Jade

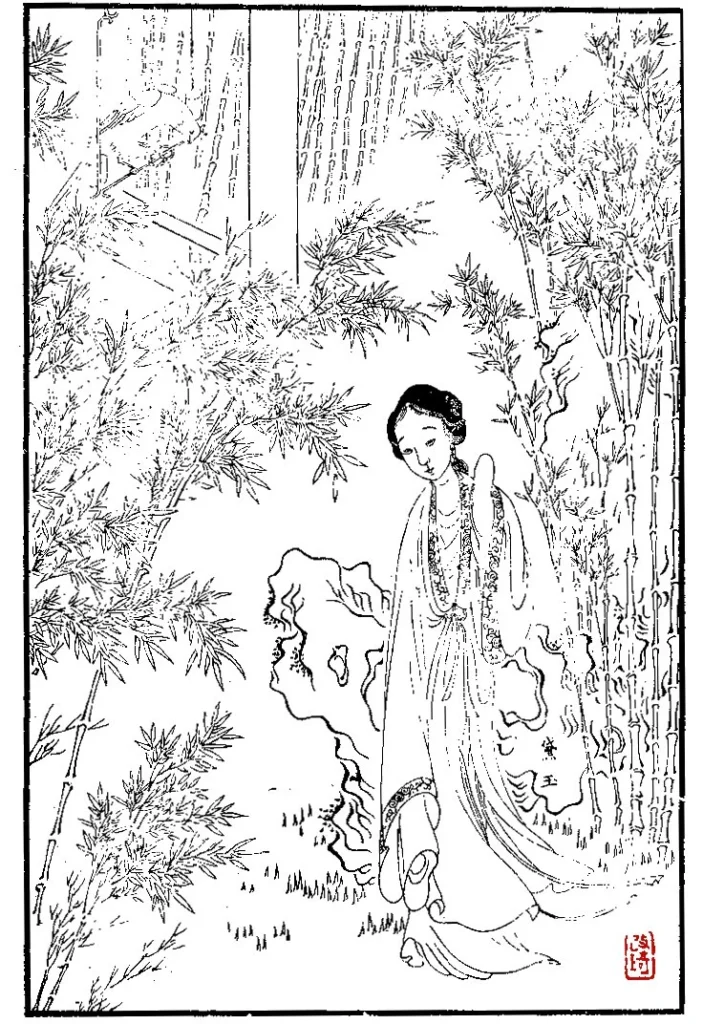

One day, at the Jia residence, arrived Lin Tai-Yü (林黛玉, “Dark Jade Lin”), Pao-Yü’s orphaned cousin. Her fragile beauty was heartrending: a pale complexion, “white as snow brushed with rose”; large eyes veiled with melancholy; fine brows “like distant smoke”; lips tinted with the subtlest rose.

Her slender frame seemed threatened by the wind; her frail health condemned her to coughs and tears. Tai-Yü is constantly linked to the willow — tree of sorrow and mourning, a remnant of her former life — and her unending sobs become the very expression of her anguish. A delicate poetess, she shared with Pao-Yü an immediate affinity, a bond at once mysterious and profound.

Yet the cruel destiny of the aristocracy imposed other choices. Their union was thwarted, and Tai-Yü’s untimely death shattered Pao-Yü’s heart, driving him into grief and madness.

Tai-Yü withered in her tears. The two adolescents lived out their tragedy without cries, in a silence carved from stone.

Jade: Stone, Soul, and Destiny

Through this tale, jade ceases to be a mere mineralogical gem. It becomes a transcendent substance, animated by a vital breath; a symbol of incorruptibility and fragile beauty; a metaphor for the human soul, destined to shine, yet always threatened with fracture.

Just as Pao-Yü and Tai-Yü each embody a form of jade — one luminous and precious, the other dark and fragile — the stone becomes a mirror of the human condition. Its hardness, its brilliance, but also its vulnerability, remind us that all that is sublime is destined for impermanence.

An ancient Chinese proverb whispers: “The common man loves gold; the cultivated man loves jade.”

Gold is hoarded, but jade is contemplated. It is caressed like a poem, meditated upon like a painting, and cherished as one cherishes a soul.

A Millennia-Old and Universal Stone

A hard stone celebrated by countless civilisations, jade holds an incomparable place in the history of humankind. It is particularly associated with China, where it has accompanied culture for over eight millennia.

Under this generic name, jade does not refer to a single gem, but to a group of stones composed primarily of silicates. Their physical and chemical properties vary — hardness, translucency, colours. This diversity explains the universal fascination it inspires.

Everywhere, it was imbued with spiritual and cultural values. In China as in Mesoamerica — two worlds separated by more than 10,000 kilometres — jade was celebrated, crafted, and sacralised. This striking convergence still fuels the imagination today: mere coincidence, or a remnant of forgotten contacts between distant civilisations?

Jade in Mesoamerica: the piedra ijada

The Olmecs, the Maya, and the Aztecs attributed to jade a sacred and medicinal value. Carved into amulets, masks, or funerary offerings, it embodied the power of the gods and the continuity of life.

In the fifteenth century, the conquistadors named it piedra ijada (“stone of the flanks”), for it was believed to relieve kidney pains. From this term derives our word jade, probably influenced by local designations.

Yet the Spanish chroniclers, more concerned with the quest for gold and silver, left few accounts of the spiritual role of this stone within Mesoamerican cultures. With the conquest, these civilisations vanished, taking with them part of jade’s symbolic meaning.

Jade and the Chinese Yu

In China, jade is known as Yu, a term whose meaning far surpasses the narrow Western classification. Whereas modern laboratories restrict the definition of jade to nephrite and jadeite, Chinese culture embraces a wider spectrum, founded upon use and symbolic value.

The earliest jade artefacts — weapons, ornaments, ritual objects — appear as early as prehistory, notably in the Yellow River basin, and particularly in the province of Henan, cradle of Chinese civilisation. From the very beginning, jade acquired a poetic and spiritual dimension: it embodied beauty, purity, incorruptibility, and eternity. Certain legends describe it as fragments of the celestial vault fallen to earth. Its silky polish, the fruit of painstaking craftsmanship, was interpreted both as an aesthetic revelation and a spiritual fulfilment.

Mentioned in texts for more than five millennia, jade — chiefly nephrite — bears witness to an unbroken cultural continuity. In 1949, part of the imperial treasures was carried to Taiwan by Chiang Kai-shek: today these pieces are preserved at the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

The Hardness and Categories of Jade

The hardness of stones is measured on the Mohs scale (from 1 to 10, with diamond representing the highest value). This classification remains the most practical, though other criteria — purity, beauty, the quality of workmanship — play an equally vital role. Thus, a raw block of Carrara marble (hardness 3–4) does not hold the same value as a sculpture fashioned by Michelangelo: the artist’s hand transcends the material.

For jade, three broad categories are generally distinguished, inspired by the Chinese notion of Yu:

jades of hardness 6 to 7,

jades of hardness 5 to 6,

jades of hardness 4 to 5.

The Great Varieties of Jade

Nephrite (calcium and magnesium silicate): the first jade to be worked by humankind, used from the Neolithic period in China and by certain pre-Columbian peoples. Its hardness (5–7) makes it a resilient stone, once believed to have medicinal virtues, notably against renal colic — hence its name. It is found in China, Siberia (Irkutsk), Canada (Yukon), South America, and New Zealand. The “polar” jade of the Yukon, rare and translucent white, is highly prized; Siberian nephrites enjoy a reputation for excellence.

Jadeite (sodium and aluminium silicate): less ancient in Chinese history, it was introduced in Yunnan and above all mined in Burma from the eighteenth century onwards. Its colours range from deep green to white, with shades of lavender. Its hardness is 7.

Celadon jade: grey-blue, hardness 6.

Henan jade: multicoloured, hardness 4–6. Found exclusively in Henan province, near Luoyang, it offers a unique palette (black, white, pink, green, yellow within a single block), a challenge for sculptors.

Hsiu jade (Hsiu Yuen serpentine): a distinctive apple-green stone, recognised in China as jade, although its hardness (4) excludes it from Western classifications.

Imperial jade: an honorific designation reserved for exceptional pieces, worthy of imperial collections, distinguished by the quality of the stone and the refinement of the carving.

In China, it is common to name jades by their geographical origin — Henan, Hsiu Yuen, Yunnan, Burma. This practice bestows an identity, almost a personality, upon a mineral substance, as though it carried within it the soul of its native land. It enables connoisseurs to compare the regional qualities of a single category of jade.

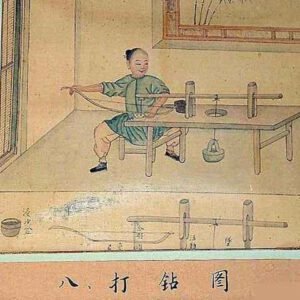

The Art of Carving Jade

To work jade is an art of patience and humility:

Conceiving: observing the raw stone, its fissures, veins, and colours, in order to select a subject in harmony with it.

Carving: revealing the forms, in constant dialogue with the material.

Polishing: the ultimate stage, sometimes repeated seven times, which brings out brilliance, softness, and depth of tone.

The hardness of jade demands tools harder than the stone itself. This arduous process reinforces its symbolic value: each sculpture appears as a victory over the inertia of the mineral, transfigured into an eternal object.

The Value of Jade

The value of jade lies as much in the rarity and beauty of the stone as in the art of its carving. Among the most difficult of stones to work, it is also, in China, the one that has inspired the greatest artistic achievements — masterpieces born of a material both divine and capricious, yet eternal. This is why certain pieces today reach staggering sums. Yet their price reflects not only the rarity of the stone: it also embodies the heritage of a civilisation, the beauty of an artistic gesture, and the enduring power of a symbol.

Conclusion

At the crossroads of science and myth, jade weaves its way across continents and centuries like an invisible thread. In China as in Mesoamerica, it was revered as a sacred substance, a shard of eternity. Studied as a mineral, celebrated as a symbol, fashioned as a work of art, it remains one of the most meaningful stones in the history of humankind.